(selective excerpts from ‘A Citizen Legislature’ by E. Callenbach and M Phillips reproduced with the authors’ permission.)

Many reformers recognise the threat of money in politics, but solutions that only deal with campaign spending have failed to reach the root of the problem. The Citizen Legislature is a scientific way to select legislators so they will be truly representative. This process worked for the ancient Greeks over more than two centuries: selection by lottery. This will yield a more descriptively representative legislature (i.e. one that looks like the society as a whole) and one not beholden to the weight of special interest donations that are having inordinate influence over policy.

A traditionally elected party-based upper house/ senate would remain as house of review.

At the birth of the American republic, as James Madison noted, members of the constitutional convention “wished for vigor in the government, but . . . wished that vigorous authority to flow immediately from the legitimate source of all authority. The government ought to possess not only, first, the force, but secondly, the mind or sense of the people at large. The legislature ought to be the most exact transcript of the whole society.” And John Adams argued that a legislature “should be an exact portrait, in miniature, of the people at large, as it should think, feel, reason, and act like them.” Electoral systems are not achieving this aim.

It is proposed to have a single House of Representatives of approximately 300- 400 randomly selected citizens (drawn from the broadest possible lists), serving three year terms, rotating out one third of representatives each year. On this sample size, the match to the population as a whole would be accurate within a statistical deviation around 2.5%. As such, the democracy would be likely to see teachers, plumbers, entrepreneurs, engineers, women, writers, immigrants, business people, retirees etc at the same ratio you see people in society.

Those drawn would be paid and work full-time as representatives, meeting daily and with the power and impetus to explore every element of the bureaucracy and public expenditures – rather than have a single minister as the point of control.

Advantages

a. significantly more representative of the population as a whole.

b. far more resistant to the use of financial inducements from powerful special interests.

c. creates a genuine difference between Lower and Upper houses, rather having a simple continuation of party aligned interests between the two houses.

d. would be ‘cognitively diverse’ which is thought to lead to better decision making. In a non-political group environment, the level of thinking among the group tends to increase toward the level of its most able members as a result of the group having and sharing a range of perspectives on the world . Refer to the Landemore paper attached below.

e. Academic papers have demonstrated that a random selected group of problem solvers outperforms a collection of the best individual problem solvers. Breadth of perspective and experience has value – value we are forfeiting in a purely partisan adversarial system. Refer to the publication from Scott Page referred below for further information.

Arguments Against A Citizen Legislature

“Its ridiculous to entrust such a serious task to random citizens.”

Proposals to give women the vote were also met with similar distrust. However, time to reflect upon, discuss and explore the concept led to greater acceptance of the idea. Resistance to the sortition idea comes generally, from an attachment to hierarchy and a lack of confidence in the people themselves. But to endorse sortition as a means of representing the people does not require believing that the people are perfect. Any town meeting, like any elected body, has a rich mixture of individuals. Some are cooperative and devoted to the common welfare, even capable of self-sacrifice. Some are venal and self-interested. Some are easy-going, some are harsh and combative. Some are quick spoken, some are slow and deliberate. Some are honest, some are devious. Some are independent-minded, some are cautious or cowardly. In the tradition of the town meeting, or of the small face-to-face democratic cultures that preceded the industrial epoch, diverse human beings met in a common place and dealt with one another, achieving the kind of agreements necessary to hold the society together in an acceptably just order. This democratic process has its irritations, its limits, its ironies. But it is, as Winston Churchill remarked, still the best system of governance humankind has yet devised, and there seems no reason why it should not be enjoyed by representatives who are truly representative.

“Short terms lead to less memory and less accumulated expertise”.

True, but expertise at what skill? At getting elected, reading a poll or meeting with lobbyists? At running a media campaign? If the goal of our democracy is one of public trust and policies serving the widest interest, then perhaps amateurism better serves this than professionalism.

“That the remaining professional senate of skilled professional politicians will out-negotiate and outflank the amateurs.”

Entirely possible. Until a comprehensive trial is conducted it is difficult to know how the two houses will interact as the nexus of continuation of party identity between the two houses would be broken.

“The Representative House, since its members would not face possible public disapproval and defeat in elections, will not be controllable by the citizenry it represents – thus their actions may be frivolous or irresponsible.”

This is a variant of the first point, and reflects a lack of trust in other citizens. However, it is suggested that the leading driver of frivolous and irresponsible decisions is financial self interest, an aspect that this model drastically constrains. It is also worth considering that the people’s power to “throw everyone out” has been diluted by the size, media systems, and corporatist (meaning any large financially powerful entity – be it a company or a union) domination of modern society. Finally, randomly-selected citizens must return to their community and face the judgement of those close to them.

“How can this group be competent to deal with the issues of a modern government?”

Do we expect, our representatives to be ‘better than us’? Are they today? A lot of the professional and technical work of drafting of legislation is done by executive employees of the government today and this would continue to be the case. Equally, this House may draw on the principle that “No law may be passed that is so complex that it cannot be understood by a person of reasonable intelligence exercising reasonable diligence.” Excessive complexity is a kind of protective impenetrability, which favours those in society able to hire lawyers who can deal with it, and would probably be greatly reduced by a Representative House, which could send obfuscatory legislation back for redrafting. In passing, it is worth noticing that the way the present US Congress deals with the work load is to sometimes pass bills en masse: just before adjournment in 1983, 200 bills were passed without discussion in one afternoon. It requires a certain elitist disdain for the citizenry to suppose that their representatives could not apply native common sense to the business of government, and a certain credulity to suppose that members of the present House are gifted with magical levels of insight.

“If I am selected, how will I manage the disruption to my life?”

A representative would be paid in the order of $200,000 annually, representing a windfall of several years’ salary for most. This will represent a saving on the present system as there is no longer an overhead for an office, staff, campaign costs and similar.

Underlying Assumptions

a. That elections yield a small homogenous group, and that random selection will yield a group capable of making more responsible decisions far less influenced by money from powerful lobbyists. The group will be more representative of society, and more likely to meaningfully deliberate and explore the issues at hand rather than taking a fixed position based on their party’s financial interests.

b. That random selection is a scientifically reliable method of securing a representative group.

c. That the citizens’ preference for judgment by a jury of one’s peers goes far back in British history for good reason. Especially in cases where punishment could be severe, we do not trust elected or appointed judges. When life is possibly to be taken away, or freedom forfeited, we prefer to have judgment rendered by a body representative, in principle, of the community. Why would we not extend this to decisions involving the expenditure of hundreds of billions of dollars in taxation revenues?

d. That a traditionally elected group will remain in the Upper House as a house of review for the citizens’ decisions.

Background and Origins

Published in a 1985 book by Ernest Callenbach and Michael Phillips, the modern literature focused on the American situation which highlighted that 95% of legislators were white male property owners (half of them lawyers), who received US$300m annually in campaign contributions. This was suggested to have led to the creation of a “special interest state”.

The true historical precedent is Athens. The ‘boule’ (council) was probably founded by Solon, the great Athenian law-giver; it was remodelled about 508 B.C. by Cleisthenes. The boule had judicial functions in addition to being, as representative of the periodic assembly of all citizens, generally responsible for the fiscal well-being of Athens. It had 500 members, who were paid for attendance, chosen by lottery from the ten “tribes” of Athens to serve one-year terms; a standing chairmanship committee also rotated (by lot) among these ten tribes.

Boule members cross-examined their chosen successors before approving them for appointment; reasons for disbarment included military service to another state, desertion from the army, squandering one’s inheritance, maltreatment of one’s parents, and prostitution. They could, if chance selected them again, serve a second term, but no more.

Their meetings were open to the public, and non-members could also speak to the body. The boule’s scrutiny of working officialdom was persistent (it met daily) and intense. As the classicist P. J. Rhodes puts it, “The Athenian democrats in their heyday believed very firmly that experts should be answerable to the people, and subjected their activities [including their financial accounts] to close scrutiny.”

Aristotle called a boule “a characteristic organ of democracy,” and all other Greek authorities regarded sortition as an essential means of equalizing the chances of rich and poor to influence government. The boule system prevailed for two centuries, and lost its power only through the growth of a class of specialized officials serving long terms: in modern parlance, a bureaucracy.

Questions for Further Study

What is the citizen’s level of trust in this system, based firstly on an initial reaction, then based on a superficial exposure to it (reading this article), and later after having had a deliberative review and discussion of this system with their fellow citizens?

What You Can Do

Being a non-incremental (thus revolutionary) change, this requires time in the public eye and to be part of the national discussion to gain acceptance. Writing letters to newspapers calling attention to this option is the most productive first step – or perhaps you could include a Facebook link to this page, showing you as a citizen of erudition, discernment, and a revolutionary disposition. Unlike a lobbying organisation, we don’t attach a prewritten form letter or email for you to sign and pass on en masse – we have some faith that you can express an informed view independently, and that the reader may even have their own innovation that they would like to propose when putting forth the concept.

Another action any citizen can undertake is to champion this alternative democratic model at a local government level. While it may take time to develop the confidence to apply this federally, citizens in some council areas may wish to consider this – especially where the traditional model of election has not delivered representatives who served them well. The newdemocracy Foundation will support citizen groups meeting with local government to advocate exploring this change – take the first step here

Clarifications

The reader should note the key difference with Demarchy is the focus on a single (large) legislature, where demarchy proposes numerous small groupings while drawing on the same core belief in the value of Sortition (random selection for a finite period).

Further Reading

- Callenbach, E. and Phillips, M. A Citizen Legislature Banyan Tree Books (ISBN 13: 9781845401085) | Also published online

- Sutherland, K. What Sortition Can and Cannot Do (Attached) | Also published online

- The Peter Principle Revisited

- H. Landemore Why the Many are Smarter Than the Few and Why it Matters Working Paper, Department of Political Science, Yale University | Also published online

- S. Page The Difference. How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools and Societies (isbn 978-0691138541)

- The Guardian draws attention to and summaries the research work of Alessandro Pluchino, Andrea Rapisarda, Cesare Garofalo, and two other colleagues at the University of Catania in Sicily on the effects of partial randomisation of a legislature entitled Accidental Politicians.

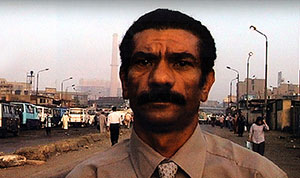

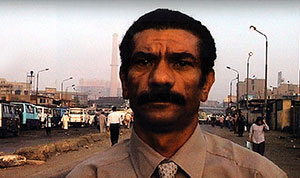

Image credit:

Image credit:

Hassan Khan

The Hidden Location, 2004

Video still from 4 channel video installation, 52 mins

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

© Hassan Khan