Lyn Carson – Research Director, The newDemocracy Foundation

What is deliberation and how does it differ from usual political discussion?

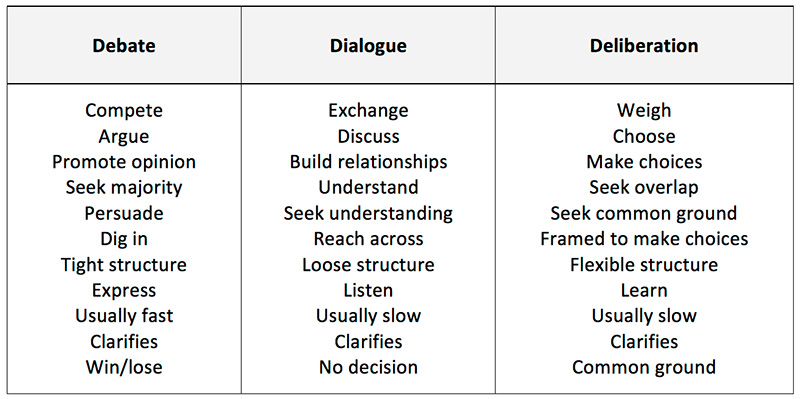

Deliberation foregrounds a very important difference in the way political discussions can occur. This note describes that difference while highlighting its importance. Here, we are speaking about public deliberation, not the internal deliberation that we each do during contemplation. In order to explain the difference between public deliberation in, say, a citizens’ jury, and what might occur in a parliamentary assembly, it’s useful to start with what it’s not (see table below).

Distinguishing between debate, dialogue and deliberation

Typically, political discussion is debate. The aim is to persuade others, and ultimately the majority, to one’s own position. It’s a win/lose situation where participants are inclined to maintain their original view. It can be angry, adversarial and swift. It can also be rational and drawn out. Dialogue can help to cut through some of the weaknesses of debate through slower civil exchange, sharing understandings by listening well, and building relationships. The emphasis with dialogue is not on decision making so much as on a respectful, clarifying exchange. These distinctions were defined by Hodge et al.

Deliberation involves both dialogue and debate (Gastil & Levine, 2005). Debate might occur when there is an invited panel of experts arguing about their various positions. Deliberation is distinctively different, even though attention is still paid to a ‘competition of ideas’ (Yankelovitch, 1991). This is because, the aim of a public deliberation is to investigate various options by hearing from experts, explore common ground, and finally reach a group decision. The fundamental difference between deliberation and debate is whether the end objective is either zero-sum or consensus seeking. In this sense, dialogue is an essential ingredient to deliberation (Yankelovitch, 1999).

What happens when people deliberate?

We know when genuine deliberation has occurred because the proof is in the type of feedback that newDemocracy hears from participants whenever a mini-public is convened. Departing citizens will speak of challenging but surprisingly respectful conversations, despite individual differences; deep exploration of issues, with a shared motivation to solve a problem; and an enhanced ability to think critically [See, Critical Thinking]. When newDemocracy collects anonymous feedback post-deliberation, randomly-selected participants almost always say they would do it again and they want decision makers to make many more, similar opportunities available to their fellow citizens (also see Nabatchi et al 2012).

It’s not a natural enterprise, this deliberative process. It requires skilful facilitation – just enough to allow the group to make its own decisions and find its own way when the going gets rough but to keep the group working well. With large groups, there will always be times when small group activity is advantageous to accelerate the process and minimise entrenched viewpoints. Exercises designed to challenge cognitive biases and test expert knowledge are used because the group will be weighing up various contested options. The group members will be establishing their own agreed behavioural guidelines, setting criteria for evaluation, gathering information, testing it, brainstorming solutions, prioritising those possibilities, agreeing on recommendations and accounting for minority opinions when consensus is not found, and collectively writing a report. The work is enjoyable and often arduous, but the group feels a tremendous sense of collective achievement once the mission is accomplished (Barker and Martin, 2011). Barker and Martin (2011) canvass the link between civic participation and happiness. newDemocracy tests the correlation between deliberation and satisfaction when we ask participants for feedback at the end of each mini-public. Here are a few comments that have been made:

- Educational and eye-opening.

- One of the most interesting and enlightening experiences of my life.

- A powerful, exhausting and compelling experience.

- Renewed and expanded my interest in bog ideas.

- A steep learning curve which eventually took into consideration all the views of the participants both positive and negative. A lot of reading between meetings but worth the effort.

- A deep sense of satisfaction and connection to my community. A sense of hope that civic-minded citizens can agree on the basics and come to consensus on most of the more complex stuff.

When a group deliberates, it is consensus seeking. This does not mean that unanimity must be attained. Indeed, minority reports are always encouraged. What is does mean is that the group is aiming to establish the extent of agreement and what each person can live with. newDemocracy always builds in the possibility for a final vote that should only occur toward the end of a mini-public; voting can be the death knell of consensus because it closes minds before all is known about a topic. Sometimes, at the end, an 80% vote in support of a recommendation is worth noting. Should it go to a vote a secret ballot is essential. This is typically done using keypads and the result is projected on a screen.

More research?

newDemocracy would appreciate robust research into the long-term impact of mini-public participants which extends Gastil’s findings (based on American criminal juries) showing the positive effect of deliberation on political efficacy (Gastil & Dillard, 1999). Nabatchi (2010) discusses various attempts to prove or disprove the link between public deliberation and the efficacy effect. Our collection of participants’ feedback immediately after a mini-public suggests this occurs but a longitudinal study would make a significant contribution to the body of knowledge.

References

Barker & Martin, B (2011) ‘Participation: The Happiness Connection’, Journal of Public Deliberation, Vol. 7, Issue 1

Gastil, J & Dillard, J P (1999) Increasing political sophistication through public deliberation’, Political Communications, 16: 3-23

Gastil, J & Levine, P (2005) The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century, Jossey-Bass

Hodge, S, Bone, Z & Crockett, J, (n.d.) ‘Using Community Deliberation Forums for Public Engagement: Examples from Missouri, USA and New South Wales, Australia’ Accessed 22 March 2017

Nabatchi, T (2010) Deliberative Democracy and Citizenship: In Search of the Efficacy Effect, Journal of Public Deliberation, Vol. 6, Issue 2

Nabatchi, T, Gastil, J, Weiksner, G M & Leighninger, M (2012) Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement, Oxford University Press

Yankelovitch, D (1991) Coming to Public Judgment: Making Democracy Work in a Complex World, Syracuse University Press

Yankelovitch, D (1999) Magic of Dialogue, Allen & Unwin

* newDemocracy is an independent, non-partisan research and development organisation. We aim to discover, develop, demonstrate, and promote complementary alternatives which will restore trust in public decision making. These R&D notes are discoveries and reflections that we are documenting in order to share what we learn and stimulate further research and development.